In December 2015, Sven Haakanson led an extraordinary month-long program at the Burke Museum which saw part of the main level foyer turned into a work space, smelling sweetly of red cedar, resonating with the rhythmic scraping of wood planes. Sven, students, Burke and UW staff, and curious museum visitors worked together to build a full sized Angyaaq, a twenty-five-foot open boat, in addition to eleven oars.

For over a thousand years, Sugpiat peoples across the Alaska Peninsula, Kodiak Island, and Prince William Sound regions used Angyaat (pl) for transportation, hunting, warring, and fishing. The boats were important symbols of wealth and power. In the early 1800s, Russian settlers occupying the area took and destroyed Angyaat because of their practical and symbolic value. These acts of oppression virtually erased this kind of boat by the late 1800s; while remnants exist in archaeological sites, an Angyaaq has not been built in the Kodiak region for over 150 years.

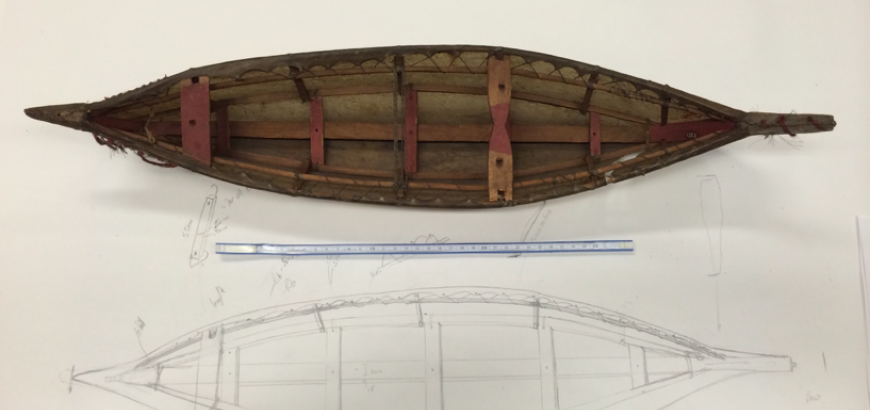

Sven came across a model Angyaaq at the Burke, one of thirteen models he has seen in museum collections from around the world, and was compelled to learn from it. The full-scale reconstruction in the Burke in December was one experiment in a larger project that redefines what it is to learn by doing. How to grasp knowledge of a thing, from a thing alone? How to care for it, transform it, build it anew? In 2014, Sven worked with the Burke Museum and the village of Akhiok on Kodiak Island in making models, and then in 2015 they scaled this up to make two full-sized Angyaat. There has been great coverage of different components of the Angyaaq project on the Burke Museum website, on the blog Incluseum, and the Tulalip News. For Anthropolog, we focus on reconstruction as research and as pedagogy.

Jenna Grant: First, can you describe the Angyaaq itself. What are its qualities, what distinguishes it from other kinds of open boats?

Sven Haakanson: This boat is unique because of the bulbous bow that distinguishes it from other traditional boat made out of skins in Alaska. The frame is made from driftwood and covered with marine mammal skins, sewn together with sinew. This boat was designed for transportation and to handle the extreme weather that is common in this region.

Jenna: How does reconstruction work as pedagogy? Within art, for example, there is growing interest in making models and reconstructions as a research and pedagogical practice that enables one to learn about embodied knowledge of the maker and qualities of materials (see, for example, Rebecca Sakoun and Florian Göttke work Boas’s models and reconstructions in the Dahlem Museum). How is reconstruction an important research method for anthropology?

Sven: Reconstructing this boat as a pedagogy to teach, share, and inspire lost knowledge is just one of many examples of methods that anthropologists, indigenous communities, and historians can use to reverse the loss of traditional knowledge within the Tribes. For the past two hundred plus years, objects and knowledge have been taken out of communities by visitors and anthropologists and stored in museums, libraries, and homes. Sadly, many of these objects have never been returned to the communities in ways they can use, in ways that help them understand how their ancestors once lived. For the past sixteen years I have been collaborating with museums from around the world and with Sugpiat communities so they can use archaeological, historical, and ethnographic collections to reestablish traditional knowledge in a living context.

The Angyaaq is the largest project undertaken thus far—from a model to a full-size Angyaaq in two years! We have been able to inspire others to do similar work in their communities. Actual physical pieces are now being seen as an embodiment of knowledge and history, knowledge which can be accessed through techniques such as reconstruction. This way of using pieces from museums and personal collections to teach, learn, and inspire has changed the role of anthropological research. We do not just collect data; we bring objects, and techniques of working with objects, back to the communities they came from to be used once again. The Angyaaq is just one example of thousands of pieces and histories yet to be told, shared, and used in the present. The original model was a catapult for starting this process and carrying it forward into a full size boat that was nearly lost to time.

Jenna: What are your plans for this summer? Are you building on Kodiak? If so, will it be a similar process to what you did at the Burke?

Sven: My goal for the spring is to finish the Angyaaq at the Burke Museum and to launch it in Lake Washington to test it out. his summer we will finish the one in Akhiok using the same techniques that we used at the Burke, from wrapping it with fabric, sewing it together to painting and carving the paddles. It has been a wonderful process because it shows how we can go from lost knowledge to lived knowledge through museum collections that are not situated within a community.

Jenna: How have people responded to the Angyaaq projects?

Sven: The response has been one of excitement and appreciation because this project is built from years of trust and open collaboration with the communities on Kodiak. Constructing the Angyaat takes a community of individuals volunteering, donating, and sharing their knowledge. The Angyaaq project is just one example of how we can help communities take ownership of knowledge and celebrate their rich histories.