by Joss Whittaker

Stumbling on things I hadn’t planned to investigate is one of my favorite parts of field work. My archaeological research, in the remote Aru Islands of eastern Indonesia, is about old settlements. But while doing this work I also became fascinated with the development in the present, particularly in the archipelago’s capital Dobo. Building houses there relies on a cottage industry of coral breakers. Men and women pry coral from the mudflats flanking the harbor, hauling it ashore in dugouts. By the beach, adults and children crouch near piles of coral boulders, often in huts that protect them from the sun, whacking the chunks with hammers and machetes into golf-ball-sized krikil (gravel), which sells for around $2.80 per fifteen-pound bag. Krikil is cheaper and lighter than concrete, but almost as strong: ideal for the houses, shops, and rather excessive ministry buildings that have transformed the isolated metropolis in a short while.

Building with coral in Aru is not new. On the island of Ujir, where I lived and worked for most of 2018, people have built with coral for a long time, including house platforms, village walls, and fortifications—the innovation in Dobo was to mix krikil with sand and cement. The most enigmatic ruins of Ujir are little enclosures of coral blocks and plaster, with arches and sculpted decoration. Villagers explained them differently: a Portuguese fort, an outpost of the Sriwijaya Empire, temples, or a cemetery. I didn’t dig inside them because I didn’t want to risk disturbing any unknown burials. I did ten small excavations around them but didn’t find a single artifact. This was a surprise because my other excavations on Ujir usually turned up a handful of potsherds. Perhaps someone kept this area clean deliberately?

For about a month I excavated a site called Jakalar, far from the modern village, alongside a crew of Ujirese workers and advisors. One day a boat anchored nearby, and workers emerged to pry boulders from the tideflats and pile them in cairns, marking them with flags so they were visible at high tide. Seeing people collect coral so far from the capital made me wonder: were residents of Dobo pulling materials from further out? I could imagine people exploiting Aru’s surviving reefs for the capital’s expansion. In this case, though, the demand was local: the coral went just a few miles, to a seawall which would protect the village from storms. The workers cemented the coral blocks together, afterward covering them in a smooth layer of concrete.

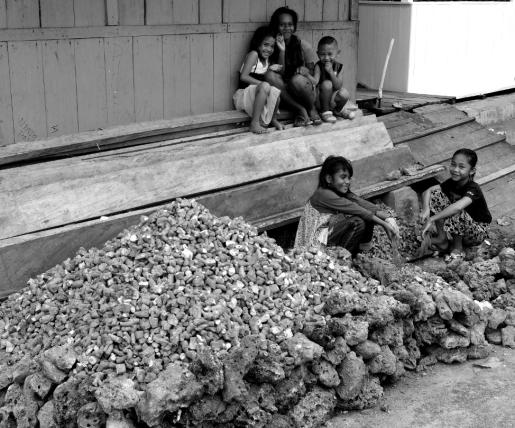

Coral breakers are everywhere in northwest Aru; they extract an overlooked, labor-intensive resource. In fact, that visibility spurred me to photograph the coral piles, and the people reducing them to gravel, on my strolls around Dobo and Ujir (I have shared many of my fieldwork photographs on my Instagram account at https://www.instagram.com/visions_of_aru/). To the outside observer, there are many bad things about this industry: the labor is poorly compensated and hard on the body. Women, children, and the elderly do what may be the most miserable parts of the work, namely making krikil. Further, people are ripping up the intertidal zone, which even in the polluted Dobo mudflats is still a habitat for many species. My initial thought was “Environmental ruin and oppression, together again,” and that may not be wrong. However, after watching and talking with coral breakers for most of a year, I never saw anyone extracting live coral, or taking coral from living reefs. They always collected in relatively dead places, and often where making the mudflats deeper would benefit anyone with a boat (that would be most Aruese families). The social effects are harder for me to evaluate. Is it, possibly, a way to reduce dependence on imported cement, and keep more construction money in Aru? As usual, the situation is complicated, and more research is necessary.