By Jacob Fisher

As a zooarchaeologist, Jacob Fisher is interested in understanding how people select and convert raw food to cooked products. He became particularly interested in “culinary processing” when analyzing skeletal remains—mostly jackrabbits—from Antelope Cave, a Virgin Anasazi site located in northern Arizona. The well-preserved remains came from deposits dating from approximately AD 680 and 960, and consist of bone, fur, skin, and desiccated entrails.

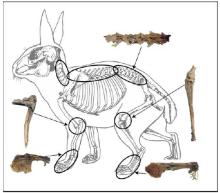

He identified how jackrabbits were butchered, cooked, and consumed at the site by statistically analyzing the body parts present, the burning and breakage patterns on bones, and the presence of desiccated soft tissues, with additional support from previous studies on the human desiccated feces recovered from the site. It appears that jackrabbits were brought whole to Antelope Cave. The feet were removed with the fur by snapping them from the lower limb. The jackrabbit was then partitioned, and meaty portions of the body like the limbs and the lower back, or “saddle of hare,” removed. After roasting and consuming the meat, the ribcage was pulverized into a meal that was briefly stewed with the leftover limb bones (broken open for their marrow), maize, sunflowers, and other plants.

The processing of jackrabbits at Antelope Cave used nearly every part of the animal to glean as much nutritional value as possible. It is interesting to look at all the steps of processing in light of the lack of fuel and water resources in the area; paleoenvironmental records suggest that the region was extremely arid at this time, devoid of large vegetation and water sources that would have been necessary during culinary processing. In addition, the fact that hunting primarily concentrated on jackrabbits suggests that the environment may not have supported larger game animals. In response, the people at Antelope Cave processed jackrabbits intensively, but minimized fuel costs by butchering the animals into smaller components to reduce roasting time, as well as cooking stews very briefly.

Although “culinary processing” is tied closely to culture since we identify ourselves largely by the foods that we eat, looking at culinary processing from an economic point of view helps us understand how past peoples overcame challenges that allowed them to live in marginal locations like Antelope Cave. Cooking is doubtlessly tightly tied to cultural norms, however, and Fisher expects that his approach is a step towards identifying the ways in which other animals were processed outside of economic limitations.

For more details on culinary processing at Antelope Cave, please visit http://www.csus.edu/indiv/j/jlfisher/jlfisher/AC1.html or contact Jacob Fisher at jlfisher@csus.edu