The Department of Anthropology is proud to have among its students three of the five recipients of the prestigious Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad Fellowships awarded to the University of Washington for 2009. These are David Citrin, Bonnie Tilland and Matthew Hale.

In this issue of e-AnthropoLog, we take an in-depth look at the research of one of the awardees, David Citrin. Through his project, “Health, Hunger, and Short-term Medical Interventionism in Northwest Nepal,” he is exploring the political implications of Nepal’s so called "health camps" within today’s

globalized world.

Health camps are a ubiquitous form of medical service delivery, development practice, humanitarian aid, and tourism in rural Nepal. They are short-term medical interventions, whether stationary or mobile, for target communities, generally lasting anywhere from a day to a week. They exist in numerous forms and attend to different medical issues, such as reproductive health and family planning, uterine prolapse, dental needs, specialized surgical work, speech therapy, mental health, and cataract treatment. Equally vast is the range of institutions and groups that organize and sponsor them. These include non-governmental organizations (NGOs) – which, in Nepal, as in most poor countries, have exploded in number – other development agencies, international study and volunteer programs, private hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, and branches of Nepal’s Ministry of Health and Population. Most notably, during and in the wake of the Communist Party of Nepal – the Maoist’s decade-long armed “People’s War” against the Nepali government – both rebel and government security forces conducted these camps.

David is looking at health camps as important, symbolic institutions of politics and healing within a particular political economic time in Nepali history. His work includes documenting and mapping the ways in which health and the delivery of short-term medical care take on a profoundly political character in rural Nepal. In particular, he is exploring the way these camps operate in a contemporary global climate where ideas of “health” and “health care” become conflated and pills, syrups, surgeries and syringes are often championed at the expense of other material and nonmaterial conditions that are also responsible for promoting and sustaining health. Examples include nutrition, clean water, peace, dignity, and hope. While both participating in and documenting these camps, David has begun to examine questions surrounding the ethics, limits, and benefits of short-term medical interventions. His study adds to other ethnographic explorations of international health care that are interested in understanding how basic livelihood resources are controlled at the ground level. His long-term goals go beyond documentation. David hopes that, through his involvement, he will be able to aid Nepalese people in their struggle to seek an end to suffering and sickness and to attain the means for new life possibilities in what many are calling a “New Nepal.”

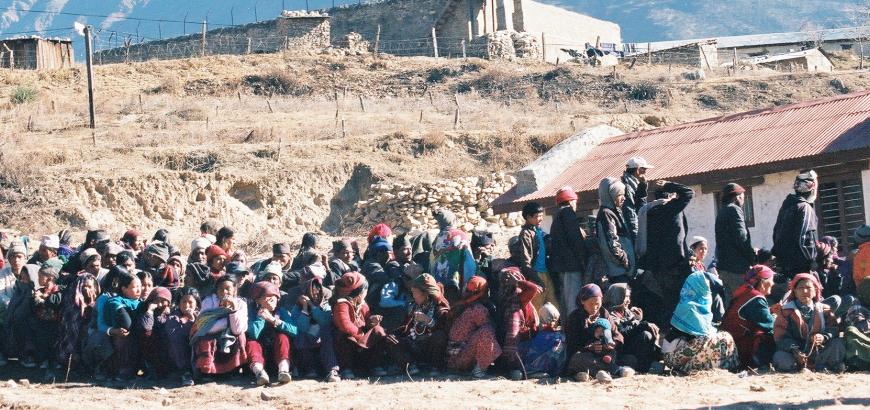

Photo captions from top to bottom:

Photos 1, 3, and 4: Long lines for health camps form early in the morning in Humla District, NW Nepal

Photo 2: David Citrin unpacking and organizing medicines for the health camp dispensary